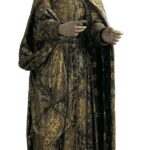

This 18th century sculpture was originally housed in the museum’s chapel. It was one of the very first pieces recorded in the museum’s inventory, bearing the number 11. At that time, it was listed under the title Saint Stephen.

A mysterious figure

The crowned figure depicted by the statue raised many questions for the museum team, which embarked on a veritable investigation to identify him. From the very beginning, however, some clues were noted:

– The clothing: the robes and cloak are adorned with fleur-de-lys, and the cloak is capped with ermine fur. These features, along with the crown, suggest that the figure belongs to a French royal household.

– The knot: his robes are cinched with a cord tied with a so-called Franciscan knot. The three loops of this knot, which adorned the robes of the Franciscan friars, were in reference to the three vows taken upon their entry into the religious order. Although the figure is clearly not a monk, he undoubtedly belonged to the Third Order of the Franciscans, founded in 1222, and intended for the laity who, being obliged to remain in the secular world, aspired to live according to their principles.

– The design of the shoes features chainmail, signifying that this figure also had a military role.

1st hypothesis: the Hungarian theory

An oral tradition of uncertain origin (perhaps originating with a Hungarian priest from Lyon) claims that this statue represents a Hungarian king. Perhaps it is in deference to this tradition that the statue was inventoried with the title of Saint Stephen, the patron saint of Hungary. The museum team thus had a duty to investigate this theory, all the more so because in 2011, representatives of the Association for Hungarian World Heritage requested to examine the statue.

Several theories for his identity have been advanced, including the Hungarian king Charles Robert I (1308-1342) or his son Louis I the Great (1342-1382). Both came from the House of Anjou-Sicily, a younger branch of the royal family of France descended from Charles of Anjou (1227-1285), king of Naples and Sicily, and the last son of the French king Louis VIII (1187-1226) and Blanche of Castile (1188-1252). This hypothesis would account for the fleur-de-lys, which also appears on this family’s coat of arms. Another name has also been suggested: Louis d’Anjou (1274-1297), also known as Saint Louis d’Anjou, a grandson of Charles d’Anjou and the grand-nephew of Louis IX (1214-1270), King of France. Indeed, Louis d’Anjou, who died an untimely death at the age of 23, was a Franciscan bishop, canonized in 1317.

But none of these possibilities are entirely satisfactory: Charles Robert I and Louis I the Great were not Franciscans; as for Saint Louis of Anjou, he was bishop of Toulouse, a member of the Order of Friars Minor, and never reigned as king. How then to explain the crown?

2nd hypothesis: the Portuguese theory

While research continued on the Hungarian side, the technique used to decorate the statue set the museum team in a new direction: towards Portugal.

Indeed, the decoration of the clothes (robes, cloak and shoes) was produced using sgraffito, a technique which involves making two successive coatings, in this case a golden one and a dark grey/brown one, and then scratching the second coating (grey/brown) to reveal the first (golden). This technique was introduced in Europe by the Portuguese, who traded with Japan in the 16th century and discovered a similar decorative technique used there. Sgraffito sculptures could be found in Portugal starting at the end of the 16th century. The Sao Roque Museum in Lisbon houses two of them, depicting St. Francis Xavier and St. Ignatius of Loloya, dated from the 17th century, and very similar to the one in our collection.

Moreover, the Portuguese royal family who reigned from 1093 to 1383 descended from a younger branch of the House of Burgundy, itself a younger branch of the Capetian kings of France. The first king is Alfonso I (1109-1185), son of Henry of Burgundy (1066-1112), Count of Portugal and youngest son of Henry of Burgundy (1035-1074), Duke of Burgundy and himself grandson of the French King Robert II, the Pious (972-1031). However, this family never used the fleur-de-lys as a symbol, and none of its kings were Franciscans.

Sculpture of Saint Francis Xavier with sgraffito decoration, 17th c., Sao Roque Museum, Lisbon, Portugal

3rd hypothesis: a Portuguese artist, a French king

We approached the curator of the Sao Roque Museum, João Miguel Ferreira Antunes Simões, who put forward a third theory: it could be a Portuguese statue, but the king depicted might be Louis IX (1214-1270), King of France, who was canonized by the Catholic Church in 1297.

This hypothesis would adequately explain :

– the crown and the fleur-de-lis on the clothing, Louis IX having been king of France;

– the Franciscan knot, as Louis IX belonged to the Franciscan Third Order;

– the chain mail shoes, Louis IX having led the seventh (1248-1254) and the eighth (1270) crusades, in which he died.

According to the curator, statues of St. Louis are very common in the chapels of the Franciscan Third Order, as are those of other saints who are also members of the Order, such as St. Elizabeth of Hungary (1207-1231). It could be that this statue originated in a chapel in northern Portugal, and that it was removed during the French invasions of 1807. Indeed, there are many cases of ancient Portuguese art being carried away by soldiers and petty officers and given to parish churches in their homelands. The statue representing Saint-Louis, King of France, may have aroused particular interest among members of the French military.

At present, this theory seems to offer the best solution to the various clues found on the statue, and considering the particularity of the technique used. However, one detail still raises a question: the fact that Saint Louis is depicted with a beard… which would be unusual, but not impossible. In any case, the investigation continues!